Comprising 99 articles and 173 recitals, laws don’t come much bigger than the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

It’s the first major shake-up of EU data protection law in two decades, and the final text was more than four years in the making. So how did we get here? We take a closer look at GDPR in the context of Europe’s relationship with data protection…

The first data protection laws

Rewind to the late 1960s and early 70s; a time when a 16-bit “minicomputer” could practically fill a room. Computerisation meant that the way in which organisations could store, access and process data was changing. Data was becoming a commodity – and this gave rise to concerns. Not least, were these new data controllers acting responsibly?

The German state of Hesse introduced the world’s first data protection law in 1970 – followed shortly after by several more individual German states.

In 1973, Sweden was the first country to regulate data processing on a national level. Sweden’s Data Act meant that only registered persons or organisations could use computerised information systems to process personal data. The country also became the first to set up an independent data authority to oversee compliance.

These two principles of registration and independent oversight would become important elements of the Europe-wide data protection framework.

Why data protection became a European issue

Why should Europe get involved with data protection?

Well, let’s move forward to the late 70s. By this time, computerised data processing was getting a lot smarter. The Council of Europe called it “information power”. Instead of just using computers for quicker data storage and search, the information stored on automated data records was starting to influence the relationship between people and organisations.

We were still a long way off from IBM Watson, but companies and governmental organisations were moving into an age of data-driven decision making.

It was actually the Council of Europe (rather than the EEC) who took the lead on this. The whole point of the Council is to uphold European human rights. So let’s say a European citizen is denied health insurance because of incorrect data held on a mainframe computer – or an employee discovers that their payroll details have been leaked to an outsider without their knowledge. In the opinion of the Council, these were most definitely human rights issues.

So in 1981, the Council of Europe passed Treaty no.108: Convention for the protection of individuals with regard to automatic processing of personal data.

Under it, Council member states agreed to pass their own laws that delivered a certain minimum level of protection to citizens, with emphasis on the following areas.

- Specified levels of security measures for data files taking into account its vulnerability and how it is stored (in what was still a mostly hacker-free world, the emphasis was squarely on physical protection!)

- Safeguards for data subjects (including the right to know what data is held in relation to them, who holds it and the right to rectify erroneous information)

- Effective data protection where data flows beyond national borders

- Suitable protective measures concerning sensitive data (e.g. children, medical records and records relating to criminal convictions)

Bringing everything together: the Data Protection Directive

Let’s say each European country enacts its own data protection legislation. So long as each country’s new laws cover the Council of Europe’s basic principles of data protection, what’s the problem?

There are lots of differences between Strasbourg and Brussels! While the EU and European Council of Ministers have a lot of shared goals, Brussels is working to a slightly different set of priorities…

Remember the EU’s four freedoms (goods, capital, services and labour)?

Well, let’s say that Country A enacts a fairly basic data protection law. It covers just about enough to ensure compliance with the 1981 treaty – but that’s pretty much all it contains.

Country B takes a different approach. It grants new rights to individuals and places obligations on organisations that go far beyond the reach of the treaty.

The upshot? Because of the extra obligations on data controllers, doing business in Country B might be a lot harder than in Country A. This was exactly the type of “stealth” trade barrier that the EEC was trying to remove…

The solution? Draw up a detailed, comprehensive system of data protection for the whole of Europe.

Eventually, this blueprint arrived in the form of the 1995 Data Protection Directive.

This contained the following key features:

- A broad definition of “personal data”. It included any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person. As long as anyone could the make that link between the data and the person. (so long as someone – and not necessarily the data controller – could make that link between the data and the person).

- Transparency and consent – including a right for data subjects to be informed when personal data is being processed. Crucially, it included a ban on the processing of personal data for direct marketing purposes where the data subject had objected to this.

- Legitimate purpose and proportionality: data processing must be for a specified purpose – and most not be held onto for longer than that purpose.

- Supervision. Each member state was required to set up a register of data controllers – and a supervisory authority to ensure compliance (and levy penalties!).

GDPR: From Treaty to Directive to Regulation

In the early 80s – an age of increasing computerisation, we saw the Council of Europe tell its members to go and pass laws to ensure that the basic freedoms of individuals were respected.

A decade later, this wasn’t enough. There was far too much scope for big differences in the types of laws member states passed – hence a clearer, more detailed blueprint in the form of the Data Protection Directive.

But here’s the thing about a directive: member states still have quite a lot of leeway in how they are transposed into national law. In other words; so long as the directive’s objectives are met there’s still scope for quite significant differences in data protection between countries.

GDPR is different. Because it’s a regulation, it comes into force immediately and automatically in May 2018. There’s no scope for divergence! “Harmonisation” is what the EU wants – and a regulation is seen as the only effective way of getting it.

GDPR: a “future-proof” law?

Lawmakers move slowly (especially if you have the interests of 28 member states to take into account). But tech moves quickly.

Within a decade of the 1995 Data Directive coming into force, Google, Amazon and Facebook would all burst onto the scene and the first iPhone was just around the corner. In a decade’s time, GDPR will still be with us – but who knows what shape “personal data” might take by then.

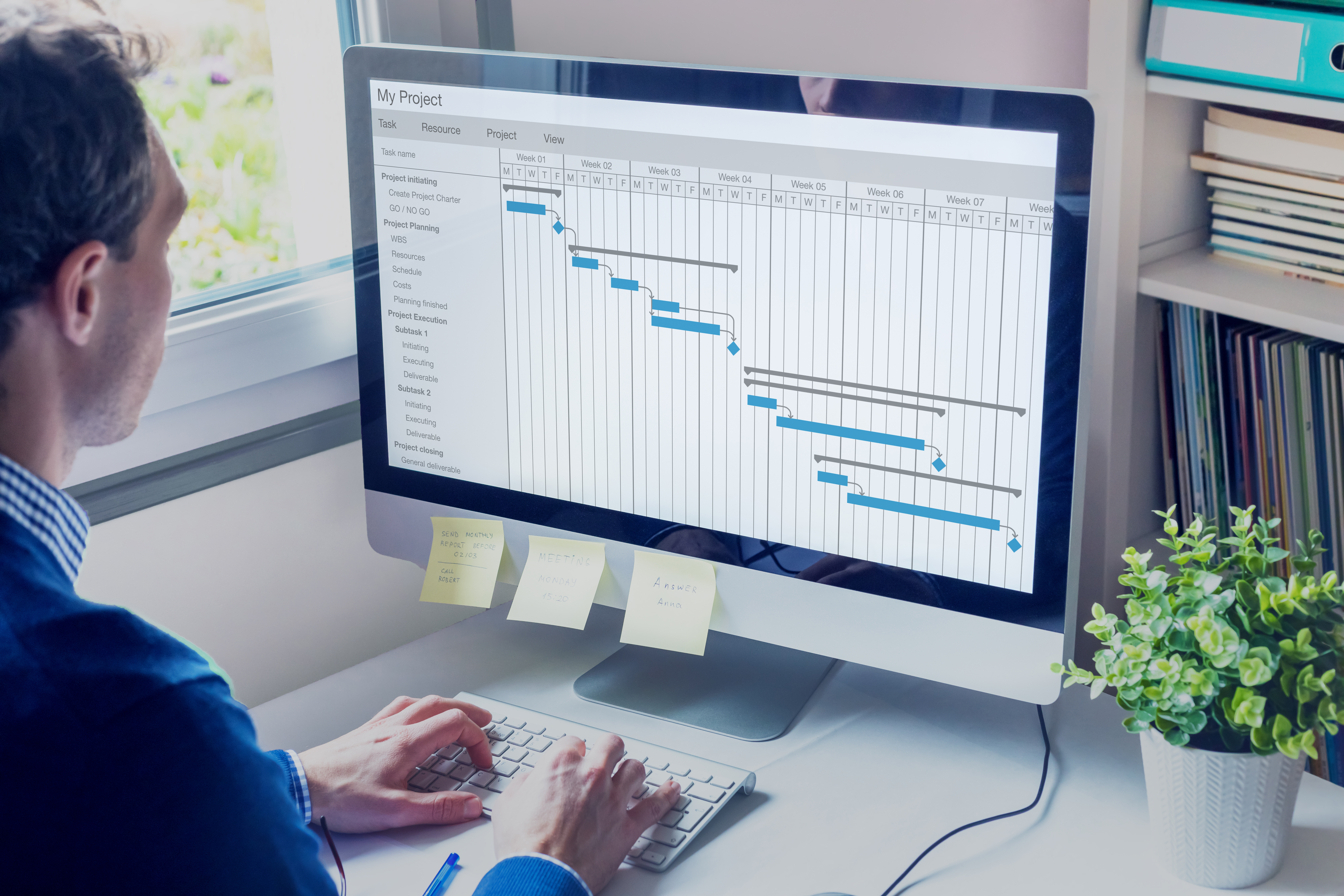

The new law has to be fit for the future; hence one of its most important principles: data protection by design and default. Whatever might be around the corner – and whatever new technologies and services you might put to work in your organisation – the regulation requires you to establish the following:

- What new personal data processing activities are involved?

- How might the rights of data subjects be impacted?

- What do I need to do to ensure that those rights are upheld?

The tech will change – but this approach will still apply.

Alongside this comes a raft of new rights for individuals (such as the right to data erasure and to have data transferred to other controllers). You can get the full lowdown on all of these by browsing our GDPR resource centre.

With GDPR, the EU evidently thinks that it has a law fit for the future. And companies who process personal data need to take a similar approach…

By bringing on board the ability to map your data estate, to enable customers to exercise their new rights and to get a better understanding of how data works within your organisation, data management no longer becomes a compliance headache.

Comments are closed.